Hansie Cronje: An unknowable enigma, and a national obsession

Luke Alfred unravels former South Africa captain Hansie Cronje, an enigmatic and divisive figure whose fall from grace became a national obsession.

First published in 2017

One night in the early winter of 2000, with the Hansie Cronje match-fixing scandal moving inexorably towards revelation, Bloemfontein’s lights went out. In an effort to escape the media scrum outside his parents’ house, Cronje had sought refuge across town, and, as the power failed, he assumed the people to whom he owed money were coming to get him. “We were all at the house of a friend, Louise Kloppers, when the blackout happened,” remembers his sister, Hester. “Hansie dived underneath a couch – he thought this was it, his life was in danger. Louise, Berta [Hansie’s wife] and I couldn’t stop laughing, we thought it was so funny. When the lights came back on and Hansie stood up, he was drenched in sweat. He definitely didn’t see the funny side. I don’t think he really forgave us.”

As the scandal broke in April 2000, Cronje was a man under siege. Over the course of several years he’d been reeled in by the bookies, his casual acceptance of their sometimes extravagant gifts giving way to an increasingly fraught relationship. With the revelations moving from denial to begrudging acceptance and, finally, a sort of grovelling apology in front of the King Commission, Cronje was suddenly a frightened man. Former friends scuttled away; the cricket administrators quickly distanced themselves. He was only 30 and his cricket career was over.

After initially making a fierce denial, Cronje later confessed to taking “easy money” from Indian bookmakers, although he maintained he never fixed a match, and his contract was terminated by the South African board in April 2000. He also admitted to implicating younger members of the side – namely Herschelle Gibbs, Henry Williams and Pieter Strydom – in his nefarious activities. As a national icon for the new South Africa, and a devout Christian who had been held up as a paragon of virtue, Cronje’s fall from grace was truly shocking and it left the country reeling.

On South Africa’s tour of India and Sharjah in March 2000, Cronje had been badgered to the point of breakdown by the bookies, taking between 50 and 60 calls a day, sometimes on mobile phones they provided. The favoured son of a white minority which had ceded power to the ANC at South Africa’s first non-racial elections in 1994, Cronje was now the object of international media scrutiny not seen since those very elections. Boiling with emotions ranging from anger to swaggering self-righteousness, South Africa couldn’t get enough of the saga. In the early stages of the fandango, even the normally sober Simon Wilde of the Sunday Times was inspired to write: “This is either cricket’s biggest crisis since Bodyline or a hoax to rival that of the Hitler Diaries.”

***

Cronje was six when the family moved to the Bloemfontein suburb of Universitas, into the very home where the media scrum would spill onto the traffic island outside in 2000. With a willow-fringed lawn and a swimming pool, 246 Paul Kruger Avenue became the site of regular cricket battles, with brothers Hansie and Frans taking on friends like Allan Donald and the three Boje brothers, of which Nicky, the left-arm spinner, became the best known.

While cricket was king, rugby was also much-loved. Tennis was played to good standard, too. Hansie sometimes travelled two hours south to Aliwal North on the banks of the sluggish Orange River, where he played tennis on the town’s famous clay courts to impress the local girls. Hester remembers doing a great deal of bowling to her brothers – born in 1969, Hansie was 13 months older than she was – during a busy but largely unremarkable childhood. When she wasn’t bowling, she was expected to field. Her timid forays to the crease were rare, done at her brothers’ indulgence.

The children were given every opportunity by their parents Ewie (Nicholaas Everhardus) and San-Marie, both of whom were originally teachers, with the former later taking an administrative post at the local university. The three Cronje siblings sang in the school choir and attended church on Sundays, where Hansie noticed his future wife, Berta Pretorius, who frequently sat with her family in the pews opposite.

Hansie was encouraged to play piano, which he did reluctantly, while Hester – who married Gordon Parsons, a member of Leicestershire’s 1996 Championship-winning side, in 1991 – chose ballet, modern dancing and drum majorettes.

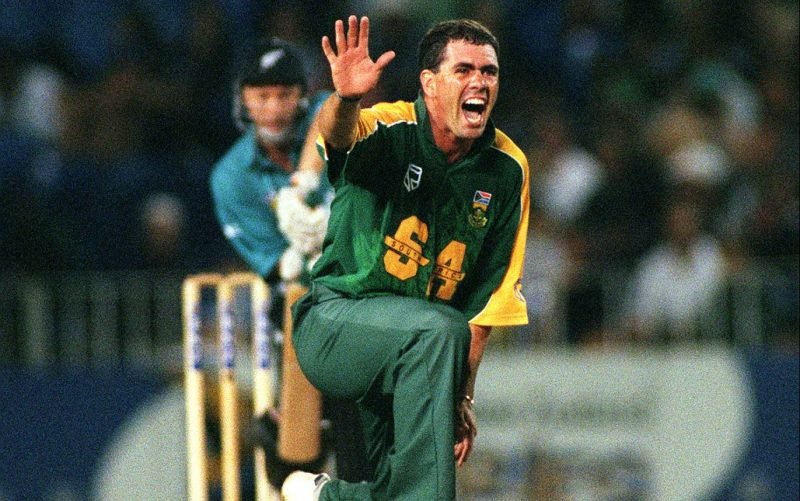

Cronje led South Africa in 53 Tests and 158 ODIs

Hansie’s dad, Ewie, learned his cricket from someone known in Afrikaans as a Boerejood – a country Jew. David Marks owned the Royal Hotel in Bethulie, the small Free State town south of Bloemfontein where Ewie grew up, and had it not been for Marks’ encouragement, the game might have remained forever exotic to the boy.

The only Afrikaans-speaker in the Orange Free State Nuffield side of 1957, Ewie was part of the generation who witnessed the transformation of cricket in the province. By the time Hansie played in that self-same Nuffield side in his final years at Bloem’s prestigious Grey College 30 years later, the team was almost completely Afrikaans.

With the quiet revolution came a growth in ambition. Ewie – and others – wanted desperately for the province to become a national cricketing force. As a sports administrator at the local university, Ewie was instrumental in widening the facilities and bringing the university onto a playing par with the other major Afrikaans universities, ‘Tukkies’ in Pretoria and ‘Maties’ in Stellenbosch in the Western Cape.

In the 1985/86 season, with Hansie in his penultimate year at school, Orange Free State, as it then was, were granted promotion to the Currie Cup from the ‘B’ division of South African domestic cricket, the culmination of years of thrift, vision and assiduous planning. For young cricketers keen to flex their muscle like Cronje and his mates, Donald and Boje, the decision provided a path to international recognition.

A subtle force in Free State’s gradual rise were a steady flow of English professionals heading south during the English winter. As a young player Ewie had fallen under the influence of the Yorkshire left-hander, Gerald Smithson, and Hansie’s cricketing maturity was hastened by the attentions of Ashley Metcalfe, Arnold Sidebottom and Neil Hartley, the Shipley-born Tyke. The chirpy Hartley was known throughout town for his second-hand brown Datsun, a battered car he encouraged passers-by to steal by occasionally leaving the doors unlocked and the keys in the ignition.

“As a boy, Hansie captained a Free State primary-school team,” says Hester. “I remember him sitting down with Neil and they came up with a sort of game-plan and wrote it all down on a piece of paper Hansie took onto the field. In the middle of everything, Hansie suddenly stops the game to look at what he’s written. ‘Get on with it Cronje,’ Neil shouts from the side. ‘This isn’t a bloody feature film’.”

Gordon Parsons was another English pro who drifted Free State’s way. By nature, Bloemfontein is a small, inward-looking town, and he bumped into Hansie early. “It was 1987 and he was in his final year at school, and because very few guys had bothered to pitch to practice, we had the net pretty much to ourselves,” remembers Parsons. “After our session he asked me straight up how I would get him out. I liked that because it showed interest and willingness to learn. I was impressed.”

Like so many other visiting pros before him, Parsons was duly invited to sample the excellent cooking of Hansie’s mother, San-Marie. Over many a plate of home-cooked food, he fell in love with the long-suffering Hester, she who had bemoaned the family obsession with cricket and bowled so many deliveries on the lawn. Hansie, meanwhile, had fallen in love with Berta and, shortly after marrying, they spent the South African winter of 1995 at Leicester, where Cronje was the county’s overseas pro.

Hansie Cronje with his brother in law and fellow Leicestershire teammate Gordon Parsons at the Grace Road in 1995

Hansie’s first years out of school were a struggle. Rudi Steyn, a Free State colleague, frequent batting partner and occasional roommate, remembers a late-night heart-to-heart as Cronje flirted with giving up the game entirely after another low score. Steyn talked him round and Cronje persisted; grooving his game, serving his apprenticeship and earning a reputation as a destructive player of spin bowling and a captain with more adventure than the South African norm. He was taken to the West Indies for South Africa’s readmission Test in Barbados in April 1992, and although he didn’t play, he was being carefully watched by the men who mattered. By the time he arrived at Leicestershire as their overseas player in 1995, he was the skipper of a formidable and widely-respected Test side.

“Nigel Briars, our skipper, snapped his Achilles at Lord’s and the captaincy was taken over by Jimmy [James Whitaker],” says Parsons. “Our whole style of play suddenly changed. Jimmy was clearly influenced by Hansie and he listened carefully to what he had to say. What people tend to forget is that Hansie, in turn, was heavily influenced by Eddie Barlow, who spent a season coaching at Free State a couple of years before that. He was great for Hansie, who struggled in his first years out of school. He made him feel a million dollars and fundamentally changed him as a cricketer. Looking back on it I think the roots of our Championship-winning side the following season were set when Hansie was with us. He averaged 50 with the bat and while Phil [Simmons] was our pro the following season, for me the foundations were set in Hansie’s year.”

The six months in England, following Cronje’s less-than-successful tour with South Africa in 1994, are remembered with great fondness by Hester. The Parsons’ two young children were often around the Cronjes and Hansie was attentive and kind during his time off. Hester tells a story about Hansie being given use of an old green BMW by Leicestershire CCC and driving down to Heathrow to meet his parents-in-law. With Berta’s folks and their luggage safely collected, a nervous son-in-law discovered that the car remote had jammed. Tired and irritable, everyone arrived back in Leicester in the cab of a tow-truck several hours later.

“I think the best was when they [Hansie and Berta] went down to Wimbledon for a day,” recalls Hester. “Hansie was a good tennis player when he was younger and he was wearing his famous baggy shorts. People came up to him regularly to ask for his autograph and he really puffed his chest out at all of the attention because he didn’t realise he was quite so famous. At the end of the day he signed his signature and the person he gave it back to had a good look at his handwriting and said: ‘But you’re not Pete Sampras!’”

***

Untainted by political interference or controversy, the mid-Nineties were a golden period for Cronje. He had taken over the captaincy of the national side from his Grey College predecessor, Kepler Wessels, and clicked instantly with Bob Woolmer, the new coach. There were disappointments – such as South Africa’s loss to the West Indies, and a rampant Brian Lara, in the quarter-finals of the 1996 World Cup – but, by and large, it was a happy, successful period for the national side, with the emergence of Daryll Cullinan, Shaun Pollock and Jacques Kallis. The carefree Herschelle Gibbs arrived on the scene as the Nineties faded and he slipped into a formidable and well-balanced side.

In the latter years of the decade, however, Cronje’s relationship with the then United Cricket Board (UCB) managing director, Ali Bacher, began to fray. He was unhappy when Makhaya Ntini made his Test debut against Sri Lanka at Newlands in March 1998, with Cronje adamant that the 20-year-old quick wasn’t ready for Test cricket. Bowling only 10 of 84.3 overs in the Sri Lankan first innings, Ntini was nervous and expensive in taking 1-57. He took the final wicket of the match in the second innings and two sticks in the second Test at Centurion, but by the time the Proteas played next, against England at Edgbaston in June, Ntini had lost his place. The transformation caucus were beginning to make their voices heard and, although Cronje won the early battle, he ultimately lost the war.

Hansie Cronje is one of South Africa’s only two cricketers (the other being Jacques Kallis) to achieve a double of 5,000 runs and 100 wickets in ODIs

Six months later the West Indies arrived in South Africa for their first-ever tour of the Republic and a watershed moment for many in the cricket establishment. The Windies’ last warm-up match before the first Test was against Cronje’s Free State in Bloemfontein, with the visitors starting impressively by bowling out Free State for 67 after posting 316. With a day-and-a-half to play, the tourists set Free State 438 to win, Cronje scoring 158 not out at better than a run-a-ball after his first-innings duck, as the hosts won by two wickets. In a career overshadowed by the later skulduggery, the innings serves as a reminder of his bloody-mindedness – and the virtue of being bold.

But the vintage Cronje of Bloem was slowly ground down through a fractious summer. An all-white side for the first Test was widely criticised as racially insensitive and the Cape-coloured Gibbs replaced Adam Bacher for the next match. South Africa only lost once to the West Indies all season, winning the Tests 5-0 and the ODIs 6-1, but the conversation had shifted. The summer was full of racial talk and, sniffing opportunity, the politicians became involved. UCB president, Ray White, made an inflammatory speech at Newlands and the cricket achievements were forgotten. Cronje, and later Donald, in his autobiography, bemoaned the mean-spiritedness of the times, with the nadir of a cantankerous season occurring when Cronje and Bacher got into a heated argument and scuffle after the last Test at Centurion.

***

Six months later and the Proteas played Australia in the semi-final of the 1999 World Cup, probably the most important match of Cronje’s career. He had cut a grim figure throughout the tournament and was on edge in the days leading up to the match. His relationship with Woolmer had become sour and the two had a mad, chair-throwing fight shortly before the match, a thrilling tie described memorably by the Daily Telegraph’s Scyld Berry as “the day when time and Allan Donald stood still and Lance Klusener kept on running”. Australia progressed to the final because they finished higher than South Africa in the table in the preceding ‘super six’ stage.

South Africa’s agony and Australia’s lucky escape – the 1999 World Cup semi-final at Edgbaston

Looking back now it is clear that Cronje was at the end of his tether as his crimes caught up with him. He had put himself in a position where he was getting cold-called by bookies, and then inviting them to his hotel room. He had incriminated the most callow members of his side and was prepared to skim off some of their earnings as a commission. The web of lies was spinning out of his control and his fall from grace was imminent.

Yet so revered was Cronje – the clean-cut boy from the platteland, the flat heartland of the country and the symbolic centre of the Afrikanerdom – that even when his crimes became clear they were greeted with disbelief by many. His former teammates felt conflicted and were unable to condemn him outright. Such were their moral and emotional contortions that Shaun Pollock, who replaced Cronje as captain for the ODI series against Australia in April 2000, dedicated the Proteas’ 2-1 victory to the disgraced former captain, saying: “We all have great respect for Hansie and this was our way of showing it.”

***

Hester tells a story of Hansie and Berta on a romantic getaway to Paris when he was playing at Leicestershire. “They lived on bread and water – he was such a cheapskate, he was always giving away his freebies as presents.” She also talks of missing him, of being frightened she’ll forget what he looked like, of bursting into tears, even now, at the mention of his name. Then she calms down and apologises, wondering what might have been had her brother not piggy-backed on that flight to George 15 years ago. When she recovers herself she tells the story of the three decaying willow trees in the family garden, which started sprouting olive leaves on the day her brother died.

First published in 2017